Why the Italy-Germany Bond Spread Is Shrinking

Favourable temporary external factors and prudent national policy choices both play a role—though the latter need to prove durable

“One key metric for investors is the public deficit, which is expected to fall below 3 per cent of GDP by 2026. Should this happen, Italy would exit the excessive deficit procedure under the Stability and Growth Pact.”

The recent narrowing of the spread between Italian and German 10-year government bonds—to around 100 basis points, a level briefly seen only in 2016 and early 2021—has caught many observers by surprise.

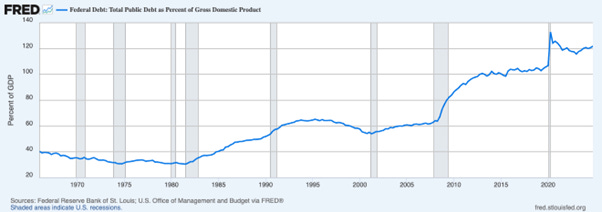

This is especially true given recent economic forecasts. Both the IMF and the European Commission have revised down Italy’s growth projections, while also projecting an increase in public debt—from 135.3 per cent of GDP at the end of last year to 138.2 per cent by end-2026.

Meanwhile, yields on German Bunds have risen by roughly 60 basis points since the start of the year—a development that, in the past, would typically have widened the spread. Clearly, markets are weighing other factors.

First, short-term interest rate expectations across the eurozone are playing a key role. Markets are pricing in a 25 basis-point cut by the European Central Bank in early June, with at least one more to follow in the autumn.

In such an environment, with short-term rates below long-term rates, carry trades—borrowing short to invest long—become attractive. This puts downward pressure on long-term yields, especially for higher-yielding sovereigns like Italy and Greece.

Second, investors are increasingly wary of the dollar. Concerns about the unsustainable trajectory of US public debt, combined with mounting political pressure on the Federal Reserve by the Trump Administration are driving capital flows toward Europe. This has strengthened the euro and boosted demand for higher-yielding European sovereigns.

A third factor is Italy’s fiscal stance. The government has adopted a cautious interpretation of the EU’s revised Stability and Growth Pact rules. Over the coming years, public spending is projected to grow at a pace below the new thresholds. This will help improve the country’s primary surplus—the budget balance net of interest payments—a key metric for debt sustainability.

Markets are also focused on the overall deficit. Should Italy manage to bring it below the 3 percent of GDP threshold by 2026, as currently projected by the EU Commission, it would exit the EU’s excessive deficit procedure. This would signal fiscal credibility and strengthen Italy’s standing in the eyes of investors.

Such a shift would also ease access to the ECB’s monetary support mechanisms, notably the Transmission Protection Instrument—a backstop that allows for potentially unlimited sovereign bond purchases in response to market stress. Access to this shield hinges on the ECB’s assessment of debt sustainability, a criterion more easily met by countries no longer under EU deficit procedures.

This “bonus” effect has been seen before. Portugal, Ireland, and Greece, after exiting excessive deficit procedures, experienced sharp declines in sovereign risk—spreads fell below Italy’s in many cases.

Finally, Italy’s growth outlook has stabilized. Forecasts for the coming years are broadly in line with the euro area average—a notable shift from the last decade, when Italy consistently underperformed. This more optimistic outlook is partly due to EU Recovery Fund investments.

In short, the decline in Italian bond spreads is due to both temporary external conditions and domestic policy choices. But to fully realise the benefits of today’s relatively lower borrowing costs, Italy must remain on a disciplined policy path.

As the recent US experience shows, earning the trust of financial markets takes time and effort. Losing it, by contrast, can happen very quickly.

A first version of this article was published in the Italian daily Il Foglio

Lorenzo Bini Smaghi

Lorenzo Bini Smaghi holds a degree in Economic Sciences from the Université Catholique de Louvain (Belgium) and a Ph.D in Economic Sciences from the University of Chicago. He has been Chairman of the Board of Directors of Société Générale since 2015. He is an IEP@BU non-resident fellow

Sustainability disclosure: red tape or strategic tool for the future of business?

SDA Bocconi - Via Sarfatti 10, Milano

The IEP@BU Mission

Founded by Bocconi University and Institute Javotte Bocconi, the Institute for European Policymaking @ Bocconi University combines the analytic rigor of a research institute, the policy impact of a think tank, and the facts-based effort of raising public opinion’s awareness about Europe through outreach activities. The Institute, fully interdisciplinary, intends to address the multi-fold obstacles that usually stand between the design of appropriate policies and their adoption, with particular attention to consensus building and effective enforcement.

The Institute’s mission is to conduct, debate, and disseminate high-quality research on the major policy issues facing Europe, and the EU in particular, its Member States and its citizens, in a rapidly changing world.

It is independent of any business or political influence.

The IEP@BU Management Council

Catherine De Vries, IEP@BU President

Daniel Gros, IEP@BU Director

Sylvie Goulard, IEP@BU vice-President, Professor of Practice in Global Affairs at SDA Bocconi School of Management

Silvia Colombo, IEP@BU Deputy Director

Carlo Altomonte, Associate Professor at Bocconi University and Associate Dean for Stakeholder Engagement Programs at SDA Bocconi School of Management

Arnstein Assve, Professor in Demography at Bocconi University

Valentina Bosetti, professor of Environmental and Climate Change Economics at Bocconi University

Elena Carletti, Dean for Research and Professor of Finance at Bocconi University

Eleanor Spaventa, Professor of European Union Law at Bocconi Law School

Pithy and to the point! As always