NATO’s 5% Pledge: Political Symbol or Strategic Shift?

Budgetary targets are politically expedient but of little policy value

That a country spends 2, 5, or 10% of its GDP on defense says little about its military capabilities.

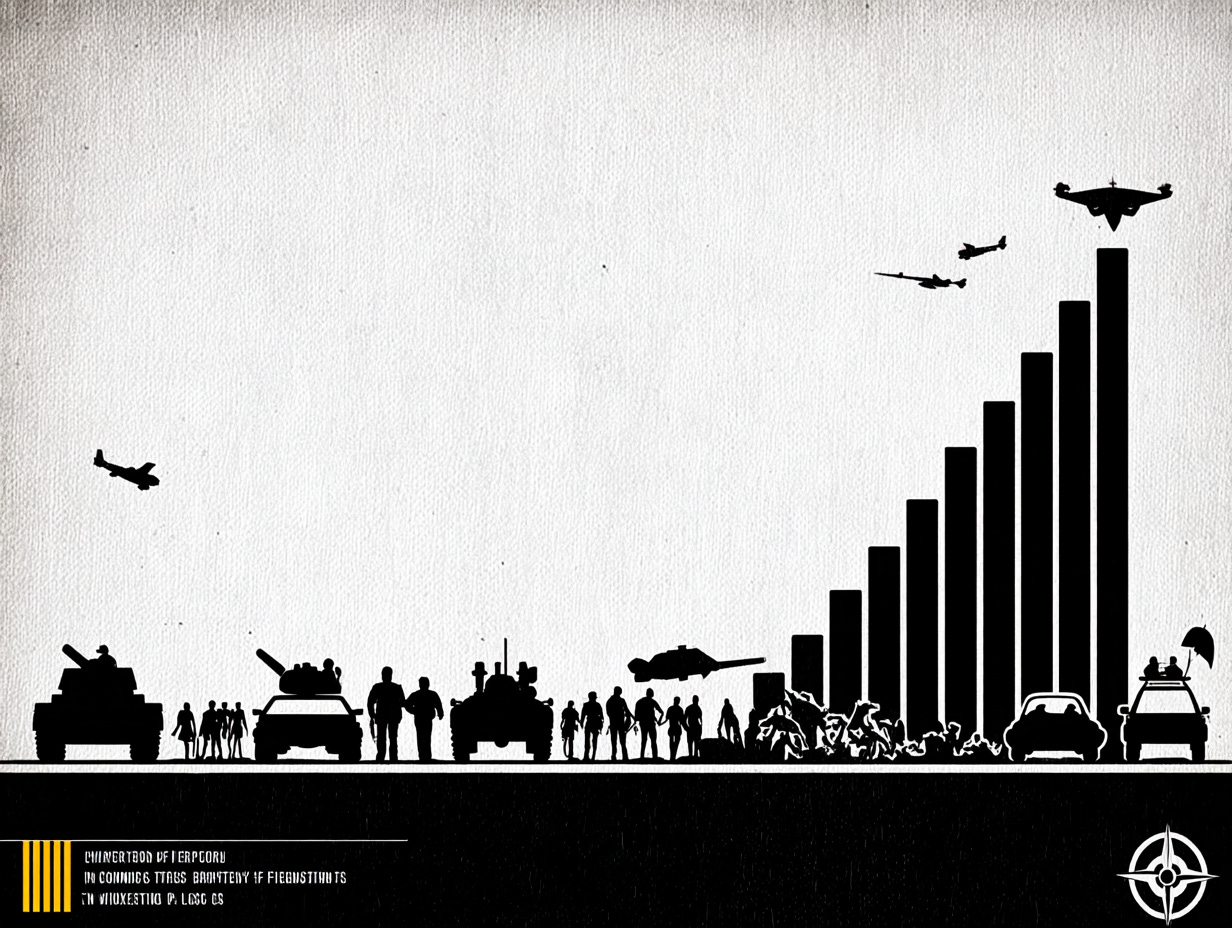

On June 24 and 25, NATO countries’ heads of state and government met in The Hague for their annual gathering. Ultimately ,the Europeans found a political solution to the request by Trump that NATO members should spend at least 5 % of GDP on defense.

All NATO Allies have committed to reach 5% of defense spending, but by 2035, and of this 5%, 1.5% will be allocated to resilience, which is politically easier to digest and implement via some relabelling of existing expenditure.

Some northern European countries had already earlier recognized that about 3.5 % of GDP for military spending was needed for their own security. Spain remained the only country that did not endorse this new spending target.

The key challenge is now whether this increasing spending will translate in superior military capabilities. For this purpose, NATO governments have endorsed a new initiative, Rapid Adoption Action Plan (RAAP), which however does not address all challenges. Finally, Ukraine remained on the agenda, but it is not clear that NATO Allies have a coherent plan to bring the conflict to an end.

Defense spending was the number one issue in The Hague. Many US Presidents before had complained that their European Allies (and also Canada) do not spend enough on defense.

Trump has upped the ante over the past few months by temporarily unplugging U.S. support to Ukraine and with not-so-veiled messages that if European countries do not spend on their defense, he won’t either.

In the end, he prevailed, and (all except one) Allies ultimately agreed to raise the spending target to 5% of their GDP by 2035.

Three considerations are warranted.

First, budgetary targets are politically expedient but of little policy value. That a country spends 2, 5, or 10% on defense says little about its military capabilities.

At the end, in other realms like education or healthcare, budgetary inputs are at best considered along with policy outputs, like PISA scores or budgetary allocations: they are never considered alone.

Second, the decision to allocate 1.5% for resilience is an intelligent political move as it permits NATO to address (or try to) one of its main vulnerabilities, namely prevent that in an interconnected world where security and defense blur, adversaries can seriously undermine one’s own stability by targeting civilian infrastructures.

Moreover, this two-tiered approach to defense spending makes the new 5% target politically easier to digest for many countries: by spending on modernization of rails and seaports, or protection of digital data, NATO governments can formally claim to support the NATO mandate.

Third, before the summit, the Spanish government announced that it would not agree to the 5%, arguing that what mattered were the capability targets, which Spain would reach even if it spent less.

This led to a last-minute political drama, highlighting however a broader policy issue: attention must be on the capabilities, not on the spending. At any rate, it is not given that by 2035 NATO allies will have met these spending targets (as they did not with the 2 % of GDP from 2014). And this leads to another major topic of the summit: defense capabilities.

At the NATO Summit, Allied endorsed the Rapid Adoption Action Plan (RAAP): a roadmap to promote the development, adoption and integration of emerging technologies into NATO Allies’ armed forces – following important initiatives launched over the past few years like NATO DIANA (Defence Innovation Accelerator for the North Atlantic) and the NATO Innovation Fund.

Three considerations are in order.

First, RAAP won’t address NATO's recurrent challenges and dilemmas, namely the fact that European countries seem culturally and institutionally unwilling or incapable of stepping into new realms without NATO support and the U.S. pushing.

Second, NATO works like an intergovernmental body, and thus it has no executive influence on its Allies’ policies. This means RAAP will depend on national-level motivation and implementation to succeed.

Finally, RAAP is centralized, top-down planned; this is not how innovation occurs.

European countries need to modernize their defenses, and quickly, if they want to work in coalition with the U.S. RAAP serves this purpose. NATO does not seem to have devised a working mechanism to ensure that such a massive increase in defense spending will be effective and efficient. The hurdles are legion, from defense inflation to industrial bottlenecks to policy planning and arms transfers.

Ukraine was the last major item on the agenda. However, the topic seems to have progressively fallen off the top priorities of the Alliance. All Allies – even the U.S. – continue to declare their support and commitment to the Ukrainian cause, but in practice, there does not seem to be a clear, coherent and shared view for the war.

Historically, wars end when one of the two sides is militarily defeated, when one or both exhaust their political and material resources, or when one of the two sides sees a change in government.

The U.S., under Donald Trump, pursues a diplomatic negotiation which, however, risks proving ephemeral. European Allies are unwilling or incapable of providing sufficient support to enable Ukraine to win. This policy space enables Russia to advance.

This leaves NATO without a clear strategy either on how to defeat Russia or on how to force it to deplete all its resources.

Andrea Gilli

Andrea Gilli is Lecturer in Strategic Studies at the University of St Andrews, Senior Advisor to the Office of the Undersecretary of Defense in Italy, and Expert Mentor of NATO DIANA (Defence Innovation Accelerator for the North Atlantic). He is also an IEP@BU fellow.

The IEP@BU Mission

Founded by Bocconi University and Institute Javotte Bocconi, the Institute for European Policymaking @ Bocconi University combines the analytic rigor of a research institute, the policy impact of a think tank, and the facts-based effort of raising public opinion’s awareness about Europe through outreach activities. The Institute, fully interdisciplinary, intends to address the multi-fold obstacles that usually stand between the design of appropriate policies and their adoption, with particular attention to consensus building and effective enforcement.

The Institute’s mission is to conduct, debate, and disseminate high-quality research on the major policy issues facing Europe, and the EU in particular, its Member States and its citizens, in a rapidly changing world.

It is independent of any business or political influence.

The IEP@BU Management Council

Catherine De Vries, IEP@BU President

Daniel Gros, IEP@BU Director

Sylvie Goulard, IEP@BU vice-President, Professor of Practice in Global affairs at SDA Bocconi School of Management

Silvia Colombo, IEP@BU Deputy Director

Carlo Altomonte, Associate Professor at Bocconi University and Associate Dean for Stakeholder Engagement Programs at SDA Bocconi School of Management

Arnstein Assve, Professor in Demography at Bocconi University

Valentina Bosetti, professor of Environmental and Climate Change Economics at Bocconi University

Elena Carletti, Dean for Research and Professor of Finance at Bocconi University

Eleanor Spaventa, Professor of European Union Law at Bocconi Law School